By Dr. Thomas Gurriet

Reflections on climbing the Technology Readiness Level (TRL) ladder in the age of Physical AI

Bottom Line

- Robotics entrepreneurs must navigate a high-stakes tension: “Move Fast and Break Things” works for software but creates unacceptable liability in Physical AI.

- Product-Market Fit is secondary when industrial demand is near-infinite; the primary risk is technical and financial feasibility.

- TRLs provide a rigorous framework to de-risk physical deployment without sacrificing the speed of innovation.

- This Reflection explores Credibility Levels as a framework for mapping technical maturity directly to stakeholder trust.

- Climbing the TRL ladder to reach these Credibility Levels allows entrepreneurs to align Agile development with rigorous standards, ensuring democratized robotics scale through institutional trust.

Introduction: The Cancer Pill

In Silicon Valley, the religion is Product-Market Fit. If you are building a SaaS platform or a consumer app, the existential question is: “Does anyone actually want this?” You launch, you measure, you pivot. You move fast and break things.

But in Deep Tech—and specifically in the emerging world of Physical AI—this advice is not just wrong; it is dangerous.

My co-founder Andrew Singletary has a perfect analogy for this: The Cancer Pill.

If I told you I had a pill that cures cancer with zero side effects for $10, I wouldn’t need a marketing budget. I wouldn’t need to do “customer discovery” to see if people want to avoid dying. The demand is infinite and obvious. The only question that matters is: Does the pill actually work?

Robotics—and specifically autonomy—is the cancer pill of the modern industrial world.

The global economy is suffering from a chronic, worsening condition: a massive labor shortage driven by an aging population. Factories are understaffed, logistics networks are fragile, and the workforce is shrinking. The industrial world is desperate for a cure. If you can build a humanoid robot that can reliably perform labor and costs less than a yearly wage, you don’t need to worry about Product-Market Fit. The demand is already there. The constraint isn’t desirability; it’s feasibility.

The Graveyard of Physical AI

When a software engineer says “Move Fast and Break Things,” they usually mean pushing code that might trigger a “404 Page Not Found” error. When a robotics engineer “breaks things,” they mean pushing code that might throw 200lbs of steel at a nearby human.

This doesn’t mean the digital world is risk-free.

- In the Web 2.0 era, the main challenge was scaling performance—Twitter famously spent years battling the “Fail Whale,” forcing them to completely re-architect their backend just to handle the massive influx of tweets without crashing.

- In today’s world, the main challenge is security—defending against cyberattacks like the Colonial Pipeline ransomware hack, which didn’t just steal data but forced a shutdown of physical fuel distribution across the East Coast.

Physical AI inherits all these digital risks, but on top of that, it faces a non-negotiable safety challenge.

In robotics, “breaking things” isn’t a bug report. It’s an injury. It’s a lawsuit.

This safety-first reality is why the Autonomous Vehicle (AV) industry imploded. A decade ago, dozens of startups promised Level 5 autonomy. They applied agile software principles to safety-critical hardware. Today, after billions of dollars incinerated, we are left with effectively one, maybe two companies truly deploying at scale.

The same consolidation is coming for Humanoids. We are currently in the hype cycle where everyone has a prototype. But the companies that treat safety as an afterthought—hoping to “patch” physics later—will vanish.

A perfect example is the recent lawsuit against Figure AI. In late 2025, their former Head of Safety, Robert Gruendel, sued the company, alleging he was fired for raising alarms about the robot’s ability to “fracture a human skull.” The lawsuit details an incident where a malfunctioning unit slashed a steel refrigerator door—a mistake that, if a human had been standing there, would have been catastrophic. This is the canary in the coal mine.

The Need for Intellectual Honesty

Embracing the TRL ladder is ultimately a way to be honest with ourselves. It forces us to be transparent—both with our teams and our investors—about the actual maturity of the technology and its ability to be deployed safely. It is the antidote to the “fake it till you make it” culture that leads to injury and lawsuits.

However, because TRLs were born in aerospace, they are often associated with slow, rigid Waterfall processes. To survive as a startup, we cannot afford the decade-long development cycles of a government contractor. We therefore need to be smart about how we apply them.

Leveraging the TRL Ladder without falling into the Waterfall Trap

The goal is to decouple the rigor of the framework from the slowness of its origin.

The Aerospace sector uses TRLs to manage risk via linear, slow-moving Waterfall cycles. The Tech sector uses Agile to manage speed but often ignores physical risk.

The successful Robotics company must walk the middle path: Using the TRL structure as the safety standard, but climbing it with Agile iterations.

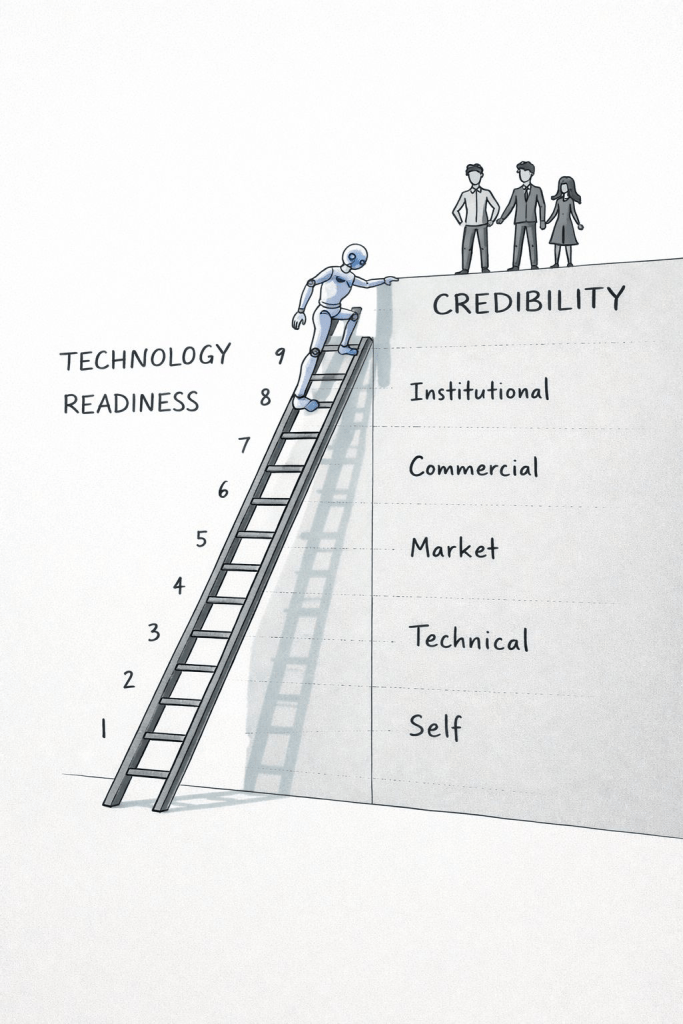

This approach transforms TRLs from a bureaucratic checklist into the tool used to ascend through Credibility Levels. Instead of a compliance hurdle, each TRL becomes a step toward a new floor of trust with capital and customers.

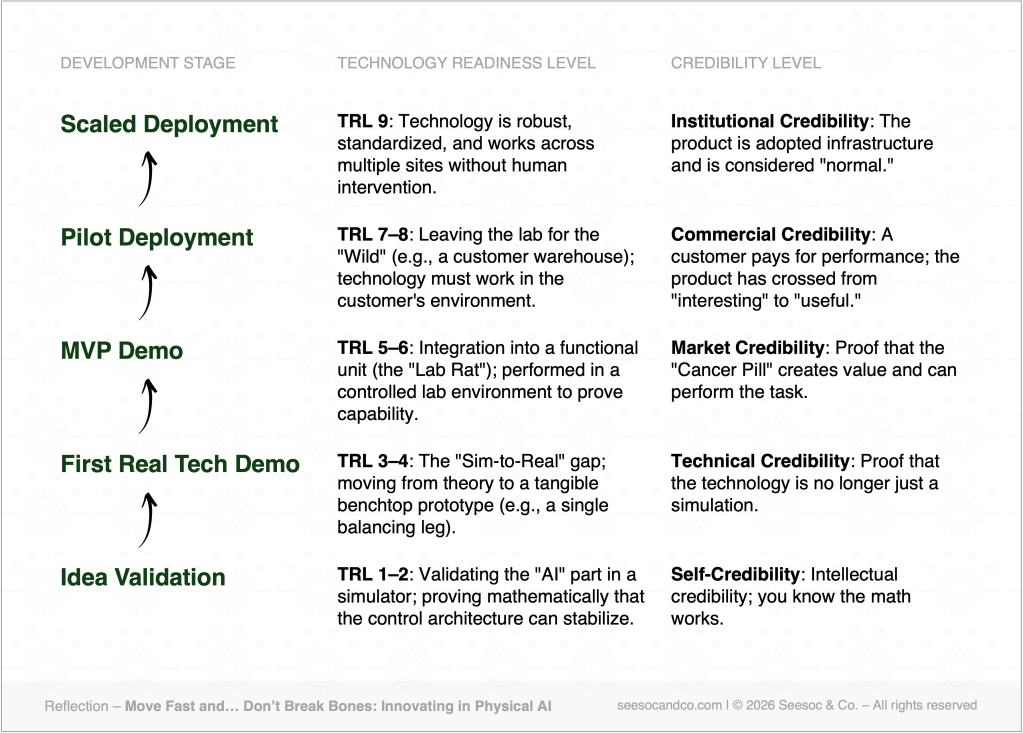

1. Idea Validation — Building Self-Credibility (~TRL 1–2)

Every breakthrough starts with an intuition. In Physical AI, this lives in the simulator.

Let’s say you’re building a humanoid called “Atlas.” At this stage, Atlas lives in Matlab or MuJoCo. You are validating the “AI” part of Physical AI. You are proving that—mathematically—your control architecture can stabilize a bipedal gait.

You aren’t convincing investors yet; you are convincing yourself. You are testing whether the physics make sense and whether the idea deserves real effort.

- The Risk: Is this physically possible?

- The Credibility: Intellectual. You know the math works.

2. First Real Tech Demo — Building Technical Credibility (~TRL 3–4)

This is the “Sim-to-Real” gap. You move from theory to tangible proof.

You build a benchtop prototype. Maybe it’s not the full robot yet—maybe it’s just a single leg balancing, or a hand grasping a cup without crushing it. This stage is about earning credibility with your technical peers and early backers.

You are showing that the idea isn’t just elegant on paper, but viable in practice. The demo is rough, wires are everywhere, but it marks the moment your technology becomes real.

- The Risk: Can we build the hardware?

- The Credibility: Technical. “It’s not just a simulation anymore.”

3. MVP Demo — Building Market Credibility (~TRL 5–6)

Now you integrate the components. The leg, the arm, and the vision system come together into a functional unit: The Lab Rat.

Atlas is standing in your lab, tethered to a safety gantry. The lighting is perfectly controlled. You film a demo where it walks ten steps and picks up a box. The goal here isn’t polish; it’s proving capability. Does it solve the problem? Can it perform the task?

At this stage, you are establishing Market Credibility—not proof that people want it (we know they do), but proof that the “Cancer Pill” can work. Investors see a machine that can do the job, even if it still needs a babysitter.

4. Pilot Deployment — Building Commercial Credibility (~TRL 7–8)

This is where the “Move Fast” crowd dies. You leave the controlled lab and enter the chaotic “Wild.”

You take Atlas to a customer’s warehouse. Safety becomes the dominant variable. In the digital world, edge cases are bugs. In the physical world, edge cases are collisions with forklifts or humans.

Credibility meets accountability here. The technology must work in their environment, not yours.

- The Risk: Will it fail unpredictably?

- The Credibility: Commercial. A customer pays not for a demo, but for performance. You’ve crossed from “interesting” to “useful.”

5. Scaled Deployment — Building Institutional Credibility (~TRL 9)

Finally, the technology becomes robust, standardized, and trusted.

Atlas is boring. It works. It charges itself. It navigates around unpredictable humans without safety incidents across multiple sites. It no longer needs evangelizing—it speaks for itself through reliability.

This is Institutional Credibility. Your product is not just proven; it’s adopted infrastructure. You have transitioned from a breakthrough to “normal.”

- The Risk: Can it scale without human intervention?

- The Credibility: Institutional. It just works

Conclusion: The Middle Path

The mistake many founders make is viewing TRLs as dusty NASA paperwork. They ignore them, rush to market with unsafe prototypes, and burn out like the early AV startups. Others cling too tightly to them, getting stuck in “analysis paralysis.”

The winners in Physical AI will be the ones who respect the ladder. They will treat safety not as a compliance hurdle, but as the fundamental product feature.

Because in the end, moving from the lab to the market isn’t just a question of what’s possible—it’s a question of who trusts you enough to let your machine walk through their door.

About the Author

Dr. Thomas Gurriet is the Co-founder and CTO of 3Laws Robotics. His background includes a decade of engineering intelligent marine systems and exoskeleton stabilization algorithms. Previously, he led high-level research focused on the safety-critical control of complex cyber-physical systems.